This is an excerpt from a free ebook by Liz Laidlaw for the FDSA Pet Professionals Program. See a link to the full book at the end of this post for more!

The science of learning is based in the academic realm of psychology. This means that some of the language of learning and cognition is jargon that may not be familiar, or may use words in a different context to their more popular usage. Trainers tend to talk a lot about the types of training and the "four quadrants," so we will discuss those here to get us started.

Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning is essentially learning through association. It's the famous "Pavlov's dog" scenario, where something that was previously meaningless to the dog (a sound like a bell, called a neutral stimulus) is paired with food (an unconditioned stimulus that causes the dog to do something instinctively; in the case of Pavlov's dogs, that was salivation). After this association is learned, the sound becomes a conditioned stimulus, and hearing the sound will invoke the same response in the dog that the food would have.

Here's Julie doing the Name Game with her puppy Koolaid! Her name (currently a neutral stimulus) is being paired with a treat (an unconditioned stimulus), so that over time Koolaid will show the same response to her name as she does to the treat.

And here is a good illustration of the end result of classical conditioning. Eileen has worked hard to pair the sound of her other dog barking with food for Clara – check out her response when Summer starts barking! You can even see her licking her lips in anticipation of the food, just like Pavlov's dogs.

In training, a comment you might often hear (originally from Bob Bailey) is that "Pavlov is always on your shoulder." This means that even when we as trainers are focused on getting behavior through operant conditioning, classical conditioning is always in play at the same time.

This is true in more than one way; new feelings and assumptions are being classically conditioned as you train depending on how the dog experiences that training, but also all previous training experiences are a factor! The relationship you have with the dog, their previous experiences of your various moods, any history in that location or in a similar context – all of these things form the background that you are working within every time you train. Being aware of this not only helps us to be thoughtful about how we set up our training sessions, but also helps us avoid being blindsided by a dog who suddenly blows up, or shuts down, or simply leaves training.

These things can feel sudden and unexpected, but are far less so once you realize the power of classical conditioning!

Operant Conditioning

Operant conditioning is learning through consequences, and through the rewards and punishments that follow a behavior. It originated in the work of psychologist B.F. Skinner, and the four quadrants that a lot of trainers talk about are rooted here.

Another term in operant conditioning that you will hear is the ABC model, or Antecedent > Behavior > Consequence, which demonstrates how operant conditioning works.

The antecedent (A) refers to whatever comes before the behavior (eg. the extended hand for a nose touch), the behavior (B) is what the dog does in response to that antecedent (eg. touch his nose to your hand), and the consequence (C) is whatever comes after the behaviour, which will act to reinforce or punish that behavior.

For a deeper understanding of operant conditioning, the Science of Training class at FDSA is an excellent choice, but for our purposes here we will simply outline each quadrant so you can see how it works. For a demonstration of operant conditioning in action through positive reinforcement, take a look at the videos in the chapter on Getting the Behaviors You Want, which illustrate the idea well.

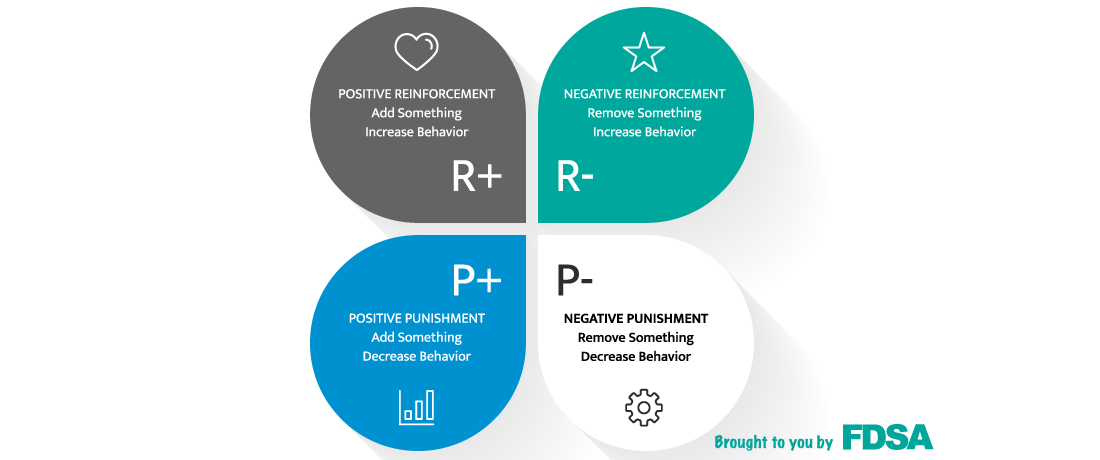

There are four areas in the operant conditioning quadrants, based on whether a consequence is added or taken away, and whether the behaviour then increases or decreases in response.

- Positive reinforcement – behaviour increases (R) when something is added (+)

- Negative reinforcement – behaviour increases (R) when something is removed (-)

- Positive punishment – behaviour decreases (P) when something is added (+)

- Negative punishment – behaviour decreases (P) when something is removed (-)

It's entirely possible to argue endlessly (especially in an online environment!) about whether a particular application falls into one quadrant or the other, or more than one! In the end, however, it can be more helpful to be aware of the quadrants so that we are crafting our training in a way that is grounded in an understanding of the science of how dogs learn, and then just go ahead and start training. Every dog is different, and often the most value will come from training the dog in front of you and remembering to check in to see how things are for that individual dog.

If your training is progressing nicely and you and your dog are happy and enthusiastic in your training sessions, then all is well! If you are not progressing, or if you or the dog are losing enthusiasm or training becomes hard work, then it's time to change things up a bit.

If your training is progressing nicely and you and your dog are happy and enthusiastic in your training sessions, then all is well! If you are not progressing, or if you or the dog are losing enthusiasm or training becomes hard work, then it's time to change things up a bit.

As students of Fenzi Dog Sports Academy and the Pet Professionals Program, you have access to the amazing online communities on Facebook that can help you reassess in those moments, and think through the issue you are having. Once you have taken a class or workshop, joining those alumni groups is highly recommended – they are full of kind, thoughtful and knowledgeable trainers who are always very willing to offer a listening ear and a helping hand when needed.

Observational Learning

Observational learning is exactly what it sounds like – learning through observation. While it is the least common in terms of how people consciously train their dogs, imitation and mimicry have been shown to work, with dogs learning new behaviours either from watching and copying another dog, or their trainer.

It is worth being aware of observational learning because, as with children, dogs are learning all the time! They watch us and learn our habits, our routines, our moods – so being aware of what we are showing them is worth having in the back of our minds.

It is also very relevant to be aware of what they may be learning from other dogs, and from the social contexts we put them in. Many a dog "learned" to be a barker at a kennel or even at flyball training! On the flip side, it is not uncommon for a braver and more confident dog to help a nervous and anxious dog to become more confident simply by watching and learning from the other.

In essence, knowing and understanding the variety of ways that dogs learn helps us to make better choices, both in our training sessions and in everyday life with our dogs.